JAYNE SHATZ POTTERY

PhD-Prehistoric Ceramics

MA- Pottery and Sculpture

BA - Art History

© 2013 Jayne E. Shatz

Japanese Overglaze Enameled Porcelains:

The Journey from Tradition to a Contemporary Palette

Japanese pottery dates back to more than twelve thousand years ago, to the first coiled pots of the Jomon era. Those skillful potters fashioned an inimitable approach to form; the wares that evolved from that foundation went on to establish impressive displays of color and decorative style.

The traditions of Japanese low fire and high fire ceramics flourished to include pit fired pottery, raku, earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. The Japanese generated a variety of ware so unique, that the world became enamored with the their aesthetics and methodology. The discovery of porcelain unearthed a white canvas for decoration that emblazoned their work with a shower of polychromatic design.

The transition from earthenware and stoneware pottery to porcelain was revolutionary for the Japanese. When I began working in clay, I looked to Asia for inspiration. My personal discovery of porcelain developed into a love affair that has remained with me for almost forty years. I spent my first decade in ceramics learning how to tame and decorate the seductive white clay. One of the most beautiful examples of porcelain manufacture I investigated was overglaze enamel painting.

Overglaze enameling is a decorating technique that involves the application of enamels to the surface of a previously high-fired glazed vessel. The enamel consists of a transparent glass like substance, a frit, which is a mixture of silica and fluxes that are fused in a second lower temperature firing that combines the metallic oxides of iron, cobalt, manganese and lead. Dependent upon the firing atmosphere, bright lustrous colors mature into iron red or yellow, copper green, manganese purple and cobalt blue. Sometimes gold or silver are married to the enamels, creating a more exotic surface, establishing overglaze enameled vessels as some of the most beautiful illustrations of porcelain manufacture. This addition to the overglaze enamel repertoire demanded an additional third firing, which was even lower than the initial enamel firings. The determined Japanese potters applied these extravagant metals to their more sophisticated pieces.

11th century Islamic potters produced overglaze enamels, as did the T’ang potters of 12th century China. Japan was manufacturing overglaze enamels on their porcelains, and by the 16th century, their highly prized Imari ware from Arita was mass-produced.

Arita ware jar, 1660-1680, Edo period, Porcelain with enamels over colorless glaze, H: 36.4 W: 26.6 cm, Arita, Japan, Freer Gallery of Art, F1970.20.

The origins of Imari-Arita ware date back to when the Japanese landscape was dotted with feudal lords, such as Nabeshima Naoshige, who brought Korean potters to Japan. In 1616, one of those great potters, Risampei, discovered a superior white-stoned clay near Arita, in the southwest province of Japan. That porcelain was the first to be produced anywhere in Japan and was originally called Imari ware, because it was shipped through the port of Imari, near Arita. Through his accomplishments, Risampei is recognized as the "father" of Japanese porcelain. Sakaida Kakiemon l, (1596-1666), mastered the techniques of overglaze enamel painting in Arita. He developed a distinctive palette of soft red, yellow, blue, and turquoise green. By 1647, he propelled the art form into great notoriety.

During the Edo period, (1600-1868), Japan was isolated from the rest of the world. Large quantities of Imari-Arita ware were exported to the Western world through the Dutch East India Company, a practice that developed into a significant business for the elusive Japan. The clean lines of this industrial ware provided the background for complex brushwork, generating outstanding work in a competitive market. Today the word Imari, or Imari-Arita, has become synonymous with Japanese porcelain. As Arita porcelain grew in popularity, the Nabeshima Clan in the Saga prefecture, northwest Japan, took steps in keeping their production and decorating techniques secret. Other feudal lords commissioned the Nabeshima Clan to make porcelain only for the elite; the law forbade the sale of Nabeshima ware to commoners. However, exportation of the wares was permitted, and Japanese ceramics was shipped worldwide. As the pottery evolved into highly decorated containers, Japan claimed a vigorous retail market. Fashionable Nabeshima ware was mass-produced, as the demand for hand painted porcelain escalated.

Nabeshima ware dish with design of reeds in mist, 1700-1740, Edo period, Porcelain with cobalt pigment under colorless glaze, celadon glaze, and iron pigment on unglazed clay, H: 5.7 W: 20.3 cm. Arita, Japan. Freer Gallery of Art, Purchase F1964.7

Japanese Kutani porcelain was produced in the mid 1650's. Once more, a feudal lord, Maeda Toshiharu, from Kutani, established the pottery climate for the area. He sent potter Goto Saijiro Tadakiyo to Imari to master the secrets of the new blue, white and red overglaze enamel porcelains. Goto Saijiro brought to Kutani a new ceramic aesthetic. The early Kutani wares were labeled Kokutani. This ware was considered representative of Japanese painted porcelain; it embraced the b o l d designs of the five traditional colors of greens, blues, yellows, purples, and reds. Goto Saijiro died in 1704, when the production of Imari and Arita style pottery reached its zenith.

Kutani style dish, Arita ware, 1644-1650, Edo period, Porcelain with cobalt pigment under transparent glaze and enamels over glaze H: 11.5 W: 45.7 D: 45.7 cm, Arita, Japan, Freer Gallery of Art, Purchase F1967.15

The brilliance of the enamels and beautiful white surfaces continue to characterize Japan's most famous porcelain. From the 18th century on, new ceramic centers were established all over Japan. The 19th and 20th centuries gave way to modern technologies in kiln manufacture and the mechanization of ceramic production. Individual artist potters emerged throughout the bourgeoning ceramic landscape. There are now many firms employing government recognized Master Craftsmen in maintaining the heritage of overglaze enameled porcelain.

Overglaze porcelain, Mimpei ware tea caddy, 1834-1835, Ogata Shuhei , (1788-1839), Edo period, Porcelain with enamels over clear glaze, H: 6.7 W: 7.1 cm, Japan, Gift of Charles Lang Freer, Freer Gallery of Art, F1900.98a-b

In the 20th century, Tomimoto Kenkichi (1886-1963), was one of these first “individual” potters of Japan. He selected overglaze enamel porcelain as his area of specialization. One of Tomimoto’s greatest contributions in the overglaze decorating field was the practice of firing gold and silver at the same temperature. Gold and silver melt differently; therefore, in order to use both on the same piece, a difficult problem arose. An additional fourth firing would have to be engineered. The gold from the third firing became tainted as it went through the cooler fourth silver firing. Tomimoto mastered a new technique by adding small amounts of gold to the silver to raise its temperature to that of gold. Then, he was able to fire both metals in one firing. He documented his discoveries, leading the way for future generations of potters to employ gold and silver on their artwork.

In the mid 20th century, the word “mingei” was coined, which means “folk art”, or art made by the unconscious collective. This phrase was termed by the Japanese art critic Soetsu Yanagi (1890-1961) and potters Shoji Hamada (1894-1978) and Kanjiro Kawai (1890-1966). They inspired a movement that rejuvenated the return to traditional folk art in Japan. Yanagi, Hamada and the English potter, Bernard Leach toured Europe and the United States in the 1950’s, lecturing to eager Western potters the aesthetics of hand made pottery and the Japanese concepts of beauty.

With this influence came a return to traditional folk pottery, and the emergence of the Art and Craft Movement of the 20th century. Many westerners worked in clay in the “Leach style”. The stoneware pottery produced was organic in appearance, single or double dipped glazes with simple surface decoration. The colors were predominantly earth tones, and while gloss glazes were employed, matt glazes dominated. The approach to porcelain was pure, with applications of clear transparent and green celadon ash glazes. During this period, thoughts of overglaze enamel painting, which required a second lower firing, evoked images of industrial ware, and ladies’ china painting classes. The technique was perceived as second rate for hobbyists. We had strayed significantly from the lushness of the Asian overglaze enamel masterpieces.

I worked in this artistic climate as a young pottery student in college. Even though it was a very exciting time to learn pottery, I felt the work created was following a particular style. It seemed that everyone in the eastern US was producing high-fired reduction stoneware. I knew there was more.

While I loved the academic roots of that earthy stoneware, my eyes lingered upon the white clays, with a glimpse toward the alluring overglaze enameled porcelains. I enjoy working in a variety of clay bodies and firing techniques, but my romance with decorated porcelain has nourished me for most of my career.

To my great joy, there has been a renaissance in the implementation of overglaze enamel painting, with artists all over the world reinventing this wonderful technique and decorating their work in rich sumptuous colors. Today ceramic artists are using overglaze enamels with metallic lusters, gilding, etching, sandblasting and yes, even decals. Some contemporary Japanese ceramists are transforming their heritage as they reinvent techniques that perhaps their fathers and villages produced hundreds of years ago. Through this resurgence, they are resurrecting the techniques of overglaze enamel decoration once more into a highly treasured art form.

Some of the finest contemporary Japanese vessel makers are working in overglaze enamels. Their work is exhilarating with a burst of color that astounds the viewer. When I look at their work, I see a consciousness that spans centuries, as if these potters have this tradition ingrained in their blood. Their work is unparalleled in technique and artistry, magnificent in surface decoration.

One of Japan’s most celebrated potters is Tokuda Yasokichi. Tokuda was born in Mashiko and started potting at 18; he took the family potter's name Yasokichi in 1988. His grandfather, the first Yasokichi (1873-1957), rediscovered many of Kutani's lost glazes and for that was made an Intangible Cultural Property by the government. While Tokuda elected to work in the overglaze enamel tradition of the Yasokichi clan, he chose to work in a more abstract style. For his mastery of Kutani glazes, Tokuda was named a Ningen Kokuho (Living National Treasure) in 1997, one of Japan’ greatest honors.

“Creation,” 1992, Tokuda Yasokichi, (1933-2009), Porcelain with polychrome enamel glazes, H: 8.8 W: 54.8 D: 54.8 cm, Komatsu City, Ishikawa prefecture, Japan, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Gift of the Japan Foundation- S1993.13

Other examples of Japan’s contemporary overglaze pottery are shown in the following beautiful vessels. While some of the vessels employ a representational style of decoration, other works exemplify a more abstract style. All the forms appear to be contained within an ethereal quality, one that enables them to “catch” the light.

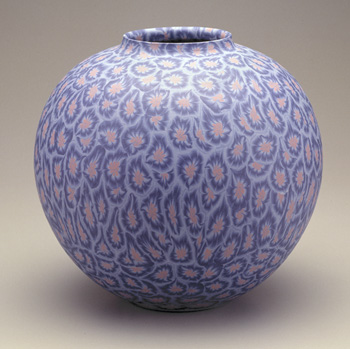

Vase with floral pattern,1990, Higashi Kuniaki , (1941-1992) Marbleized polychrome porcelain, Komatsu City, Japan, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Gift of the Japan Foundation- S1993.32

Deep bowl with linear design, 1991, Miyanishi Atsushi, (b. 1954) Porcelain with cobalt-blue stripes under blue enamel glaze H: 28.0 W: 37.0 D: 37.0 cm, Terai Town, Japan

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Gift of the Japan Foundation- S1993.36

These Japanese ceramic wares are part of the permanent collection of the Freer Gallery and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC. When you are traveling by the city, take a journey into the sublime and find these fine examples of Japanese overglaze enamel porcelains.

All images are furnished by permission from the Smithsonian Institute.

Rights and Reproductions, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

Washington, D.C. 20013-7012

Bowl, Shindo Susumu , 1992. (Japanese, b. 1952). The bowl is porcelain with black pigment under blue enamel. The bowl is painted in a rhythmic geometric pattern H 9.8, W 55.2, D 55.2. Komatsu City, Japan. The wide open form sits on an extremely small foot.

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Gift of the Japan Foundation S1993.21

Miura Shurei , Bowl, 1992, (Japanese, b. 1942), Stoneware with "peacock feather" iron glaze

H: 19.3 W: 42.5 D: 42.5 cm, Fujiyoshida City, Japan

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Gift of the Japan Foundation S1993.35

Vase.1992, Taka Akira , (Japanese, born 1936). Porcelain vase has a design of a grove of trees

with silver leaf under blue glaze, platinum and gold enamels over the glaze

H: 39.7 W: 28.3 D: 28.3 cm, Komatsu City, Japan

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Gift of the Japan Foundation S1993.23

Vase, 1990, Tamura Keisei , (Japanese, born 1949)

The Porcelain vase is painted in polychrome and silver enamels over colorless glaze

H: 53.3 W: 19.2 D: 19.2 cm, Komatsu City, Japan

Arthur M. SacklerGallery, Gift of the Japan Foundation S1993.26

Bowl, 1990, Nakashima Ken'ichi , (Japanese, b. 1949). This piece has a design of tradescantia flowers. The bowl fully expresses the tradition of Kutani overglaze enamel decoration. After the piece was fired to 1270 degrees C, it was outlined with cobalt formulated for overglaze application and then the outlines were filled in with thick applications of strong-colored enamels. Another firing at 930 degrees C fixed the enamels. H: 12.7 W: 46.7 D: 46.7 cm, Terai Town, Ishikawa prefecture, Japan

Arthur M.Sackler Gallery, Gift of the Japan Foundation S1993.28

Bowl, 1987, Mori Tatara , (Japanese, b. 1945)

The porcelain bowl is with inlaid and blown cobalt under a colorless glaze

H: 13.8 W: 48.2 D: 48.2 cm, Tobe Town, Japan

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Gift of the Japan Foundation S1993.37